A brief history of Big Sky from the canyon to the peak.

…the ski area came first and the development followed.

At destinations like Telluride and Breckenridge, ski mountains sprung up around nineteenth century mining towns with colorful histories and main streets lined with Victorian storefronts. Big Sky evolved differently. The vision for the resort started with simple geography: As any skier would recognize, Lone Mountain, a dramatic dacite laccolith that dominates the surrounding landscape with steep pitches up high and gentle flanks down low, is well suited to skiing. Which is why, in Big Sky, the ski area came first and the development followed.

And while there’s deeper history in this area now known as Big Sky, which is defined by a meadow and a solitary peak with strong shoulders, it’s a story of a landscape so rugged that prior to the Homestead Act there was little human activity on the lands around Big Sky. American Indian tribes camped and hunted along the river, but they never settled. And even after homesteaders put down stakes to scratch out a living, Big Sky had fewer than 50 residents for nearly a hundred years. Given the population density of Big Sky today—and the thousands of people who flock here in summer and winter—it’s hard to imagine that the federal government went to so much trouble to entice people to come to Montana, from land grants to the railroads to offering 160 acres to homesteaders for a song. Herewith, a timeline of the history of the land around Big Sky.

Pre-written history to the mid-1800s: Early Uses of the Land

In the mid-1800s, an Indian tribe called Tukudeka or Mountain Sheepeaters frequented the area…

Long before Lewis and Clark named the Gallatin River for Albert Gallatin, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury who financed their expedition, Native American hunter-gatherers passed through the canyon, camping along the Gallatin River. In the mid-1800s, a tribe of Indians—in Montana, native people refer to themselves as American Indians—called the Tukudeka or Mountain Sheepeaters frequented the area, hunting bighorn sheep with bows made from their horns. They were mountain hunters who moved from Wyoming’s Wind River Range west to Idaho as their mood and the animals they depended on determined.

Historians note there was a well-used Indian camp near where the Conoco station sits today. It was destroyed by prospectors in the 1890s. In his book,“The Gallatin Way to Yellowstone,” Duncan Patten describes indigenous use of the canyons dating back to the Paleo-Indian period (BCE 6000), including archaeological sites in the West Fork. “You can find obsidian chips around Big Sky, especially in the spring when the gophers are digging around,” says Barbara Rowley, author of an upcoming Assouline-brand luxury coffee table book that will commemorate 50 years of Big Sky. Native Americans would chip pieces from the obsidian cliffs in what is now Yellowstone National Park to make arrowheads.

Before settlers, European fur trappers came through Big Sky in the mid-1800s. “They depleted the beaver population and moved on to more productive rivers,” Patten writes. Up until this point, humans passed through the meadow under the mountain—but as far as science and history know, none settled permanently. Gallatin Canyon at that time was narrow and rugged, making it difficult to navigate, and the high country was too brutal for winter life.

The late 1800s: Teddy Roosevelt and Homesteaders Arrive

“It was a big black bear with that white spot under its throat. [Teddy] looked into the bear’s mouth and saw those four big tusks and said, ‘I see now how they tear up logs and trees. Just look at those tusks.”

Charles Marble, Writer, “Fifty Years in and around Yellowstone Park.”

Teddy Roosevelt hunted big game near present day Big Sky in September of 1886 with Charles Marble, who wrote about the excursion in “Fifty Years in and around Yellowstone Park.” Teddy, who was still 15 years away from the White House, shot his first bear during the 40-day expedition. “It was a big black bear with that white spot under its throat,” Marble wrote. “[Teddy] looked into the bear’s mouth and saw those four big tusks and said, ‘I see now how they tear up logs and trees. Just look at those tusks,” After camping on the West Fork of the Madison River, they crossed into Jack Creek Park and camped for several days near the Spanish Peaks Range.

Prior to Teddy’s visit, President Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law in 1862, which gave settlers 160 acres of land to lure them to the western territories, including the flat meadow where Big Sky Meadow Village sits today. Given the inhospitable landscape, the promise of free land drew only the hardiest of pioneers.

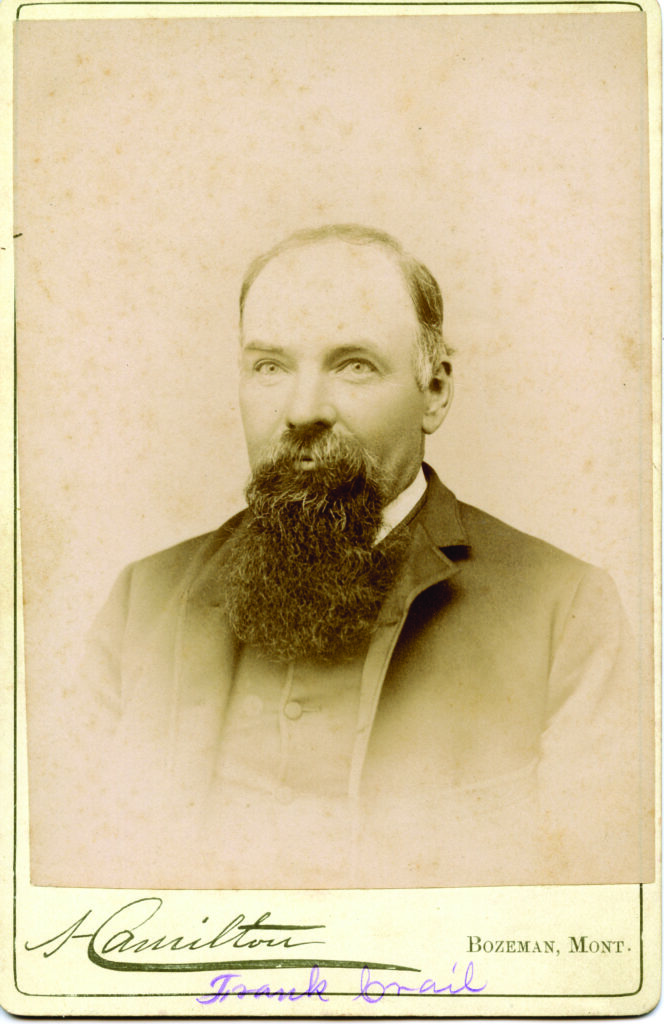

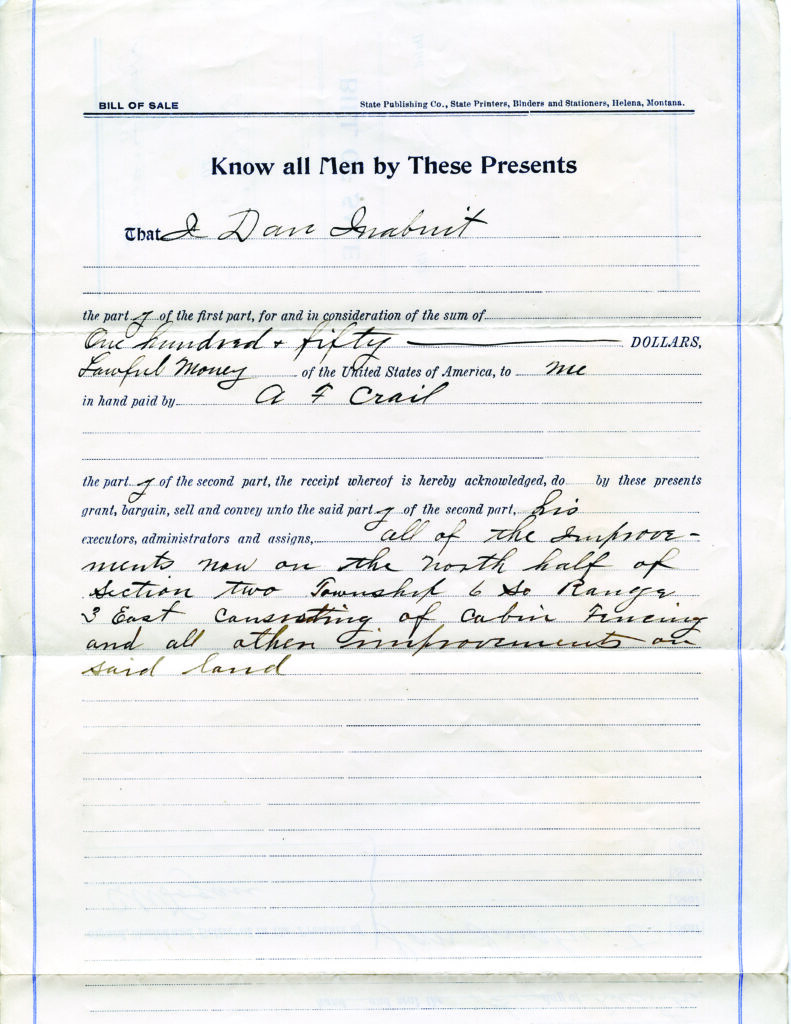

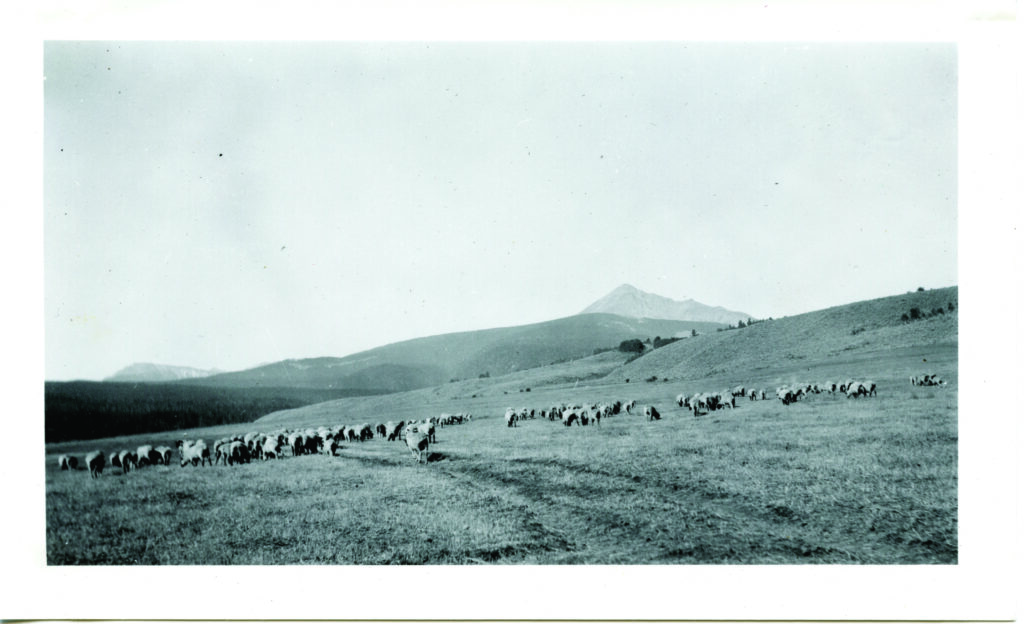

In 1901, Augustus Franklin Crail purchased a 160-acre parcel from homesteader Daniel Inabnit for less than $1 an acre. Back then, the property featured a forge, sawmill, piggery, and hay barns. Crail built his log cabins using a double dovetail joinery that made the structures sturdy enough to withstand Big Sky winters. More than a century later, two of the cabins remain on the property as the Crail Ranch Homestead Museum. The family first ranched sheep and cattle and grew Red Fife, a resilient wheat varietal that traces its history to the Ukraine. The Crails dubbed their variant Crail Fife. It could weather the harsh high-altitude climate.

Late 1800s to early 1900s: In Search of Gold

“Tom was a geologist, and he figured there would be gold here like there was in Virginia City.”

Joan Traylor, Retired Ophir school teacher, fifth generation Montanan, and armchair-historian.

In 1886, Tom Michener and his family settled just down the road from the Crail property, where the Soldier’s Chapel now sits. A cattle rancher and a prospector, Michener was sure the upper basin held untapped mineral riches—and he was not alone. The 1911 edition of Mining Science suggested the area’s claims were promising. “As a result of the recent gold find … in the West Gallatin Canyon, in Montana, all of the available land clear up to the Yellowstone National Park line has been staked out by gold seekers. The most attractive propositions lie in the old channel of the river, a short distance from the West Fork of the Gallatin.”

Michener formed the West Fork Mining Company and sold stock options for the Hercules Dredging Company. Another prospector, a German named Andrew Levinski, owned claims from Middle Fork to Lone Mountain, including a copper mine near the base of what is now Big Sky Resort. But by 1917, his registrations on the copper mine had lapsed, and two of Michener’s partners, who had “reposted” Levinski’s unworked claims, arrived at the mine. A gunfight ensued, and Levinski shot and killed both of Michener’s men. His cabin full of bullet holes, Levinski was acquitted of murder charges on the basis of self-defense and claim jumping. A few years later he disappeared under mysterious circumstances—many suspect foul play.

One of the area’s most legendary figures, he’s memorialized by Lake Levinski, near the entrance to Big Sky, and more recently, by Levinski Lodge, the resort’s newest base-area workforce housing.

Although many of the early settlers were involved in prospecting—establishing claims in search of gold, tungsten, copper, or asbestos— significant mineral riches never materialized.

They used placer mining—a technique that employs water to separate eroded minerals like gold from sand or gravel—but the gold was so fine it floated through the sluices. “Tom was a geologist, and he figured there would be gold here like there was in Virginia City,” says Joan Traylor, a retired Ophir school teacher, fifth- generation Montanan, and armchair-historian. “But, as we like to say, it didn’t pan out.”

With the gold rush a bust, the upper basin remained sparsely populated at best. In 1910, a census-taker named Henry Cowherd trudged through the land now known as Big Sky and counted just 47 souls living in 18 households— including five Crails and five Micheners.

In 1910, a census-taker named Henry Cowherd trudged through the land now known as Big Sky and counted just 47 souls living in 18 households—including five Crails and five Micheners.

In the late 1990s, the Michener property was sold and Traylor, who is dedicated to historical preservation, was instrumental in dismantling and moving the only salvageable building to the grounds of the Ophir School. She’s now spearheading an effort to move the Michener cabin once more, this time to the Crail Ranch property where the public can walk the ranch, wander trails, visit the community garden, and learn about Big Sky’s past. “The history of the Crails and the Micheners is intertwined,” she says, “and Crail Ranch is the only acre in Big Sky that’s truly dedicated to history.”

1860s to 1992: Railroads and a Checkered Past

“Big Sky’s land ownership and history is most directly tied to the railroads. All this land that today goes for millions of dollars, they couldn’t give it away.”

Barbara Rowley, Author

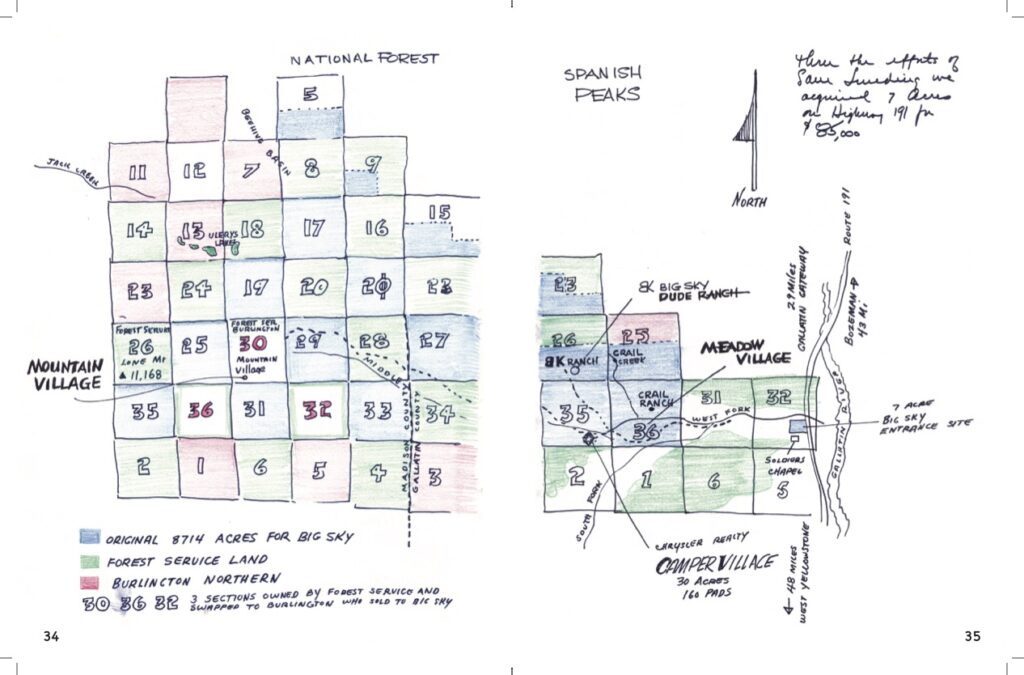

The story of how the private land around Big Sky changed hands over the years starts with a complex checkerboard that dates back to 1864, the year President Lincoln inked the Northern Pacific Railroad charter. In order to incentivize the railroad to build new tracks, the government granted the railroad 46 million acres of land from Minnesota to Oregon— much of it in Montana.

“Big Sky’s land ownership and history is most directly tied to the railroads,” Rowley says. “All this land that today goes for millions of dollars, they couldn’t give it away.” The land was divided up in a checkerboard. “It didn’t have anything to do with the topography. It was just chopped up into 640 (acre) squares,” she says. The Northern Pacific Railroad expanded into Bozeman in 1883, but no tracks were ever built in the Gallatin Canyon. Still, the land in the upper basin was valuable for its dense groves of pine. The railroad needed timber for railroad ties—every mile of track needed 2,500 crossties. Logging camps were established on Taylor Fork, and from there the cut logs would float down Taylor Fork to the Gallatin River, destined for mills downstream. The government granted the railroads eery other section of land around Big Sky, alternating with National Forest Service land and homesteads.

To access the timber, primitive logging roads were built in the canyon, which ranchers then used in summer to drive cattle and sheep to the meadows. But the land was still sparsely populated. By 1940, the census recorded only 40 people living in what would become Big Sky, dropping by seven people over three decades. Back then, there were no roads up to the land where Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight Basin sit.

In 1989, Burlington Northern, which was as much a timber company as a railroad in Montana, spun off the timber outfit Plum Creek. In 1992, Plum Creek sold the land to Tim Blixseth, who also came from the timber industry. Over those many decades, the land that now houses Yellowstone Club, Spanish Peaks, and Moonlight continued to be logged extensively.

Early 1900s to 1960s: Dude Ranching: City Slickers Channel Their Inner Cowboy

“Way back then, Tom Michener knew the value of tourism. He had pamphlets printed up that he sent back east to rally visitors… to escape their urban stress.”

Joan Traylor

Although the Crails continued to ranch on the land for some 50 years—first raising herds of sheep and then cattle—many of the upper basin’s residents turned to dude ranching in the early 1900s to entice visitors bound for Yellowstone National Park to extend their itinerary. These early entrepreneurs knew what others would discover 70 years later: Tourism was the real motherlode for the upper basin. “Way back then, Tom Michener knew the value of tourism,” Traylor says. “He had pamphlets printed up that he sent back east to rally visitors to come out to Montana and escape their urban stress.”

Starting in 1927, the B Bar K, known today as the Lone Mountain Ranch, was run as a dude ranch. The property has had different uses and owners over the years, from a boy’s camp to a logging camp to headquarters for Chet Huntley (more on him in a minute) and execs from Chrysler and Conoco during Big Sky’s startup. Today, with lodgepole guest cabins dating back to 1927, it’s a premier cross-country ski destination and dude ranch with sleigh rides, weekly rodeos, and horseback riding.

In the 1950s, Patten, whose family owns Black Butte Ranch near West Yellowstone, worked as a wrangler at Elkhorn Ranch. “I was in college at the time, and it was the best damn life a kid could have…. People came from urban centers to experience the Western way of life. You’d get to be a cowboy and ride a horse.” But then, like now, Yellowstone was also a draw. “When I was a wrangler, they’d ask us to drive guests down to Yellowstone for the day. It was always on Sundays, my day off.”

Patten remembers the days before skiing arrived. “Up by Big Sky, you had timber in the mountains and grazing in the valley. That was it,” he says. “Back then, there were about seven families living there. Dude ranching was the main thing in the ’50s. You had Covered Wagon Ranch, 320, Elkhorn, and 9 Quarter Circle.”

1920s to 1950s: Gallatin Gateway to Yellowstone

Yellowstone was established as a national park in 1872, with maybe 1,000 visitors a year showing up in its first decade. Numbers rose to a whopping 13,727 visitors in 1904. In 2021, 4.8 million people passed through Yellowstone’s gates. “The railroad played a major role in the opening up of Yellowstone Park,” Patten says. In the 1920s, the railroads battled for market share to deliver visitors to Yellowstone from different directions. “Everybody was competing with everybody else to get into Yellowstone,” he says.

In 1925, the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad ran an electric spur line into Salesville, Montana, and built the Gallatin Gateway Inn, a luxury hotel with a telephone in every room. According to Patten, the railroads promoted the canyon as a gateway to Yellowstone and even convinced locals to rename the town of Salesville to “Gallatin Gateway.” Thousands of visitors were bused through the canyon from the hotel to the west gate of the park. “When the road was still gravel, they’d need to back cars up the hills in low gear to prevent overheating,” Patten says. In the mid-1930s, the road was paved with a basic asphalt called “road-oil,” making travel from Gallatin Gateway to the park a fair bit smoother.

These days, history repeats itself. Many of the roughly one million cars that drive through the canyon each year are headed for West Yellowstone, and, not unlike the dude ranches from a century ago, Big Sky serves as a resort gateway to the park. Visitors come to Big Sky to fly fish, hike, and golf, but they’ll add a day or two in the park to their itinerary. To accommodate, companies like Karst Stage run daily shuttles to the park in summer.

“We’re a gateway for the park,” says Kristin Kern, Huntley’s niece and owner of the Hungry Moose groceries in Big Sky. “In summer, we make 75 to 100 sandwiches a day for people who are getting picked up in Big Sky and going on tours to Yellowstone.” But modern visitors to Big Sky find a resort transformed. “Even in the ’40s and ’50s, the dude ranch cabins had no electricity or water. We used kerosene lamps to read at night. It was pretty rustic,” Patten says.

1970 to 1974: Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Dream

“Nothing I’ve ever done, or seen, or accomplished— including [watching] Alan Shepard’s first space ride from Cape Canaveral— compares to my happiness in launching Big Sky.”

Chet Huntley

From 1956 to 1970, Chet Huntley co-anchored NBC’s nightly news program with David Brinkley, attaining celebrity on par with John Wayne and The Beatles. But before he was a broadcast icon covering war, elections, and assassinations, Huntley was a third-generation Montanan. He was born in a railroad depot in Cardwell, Montana (his father was a telegraph operator for the railroads). “He really did have a lot of Montana manure on his boots,” quipped The New York Times in 1974.

Huntley often returned to Montana to fish and ride horses. Using connections he made through NBC, he partnered with a handful of investors including the Chrysler Realty Corporation to develop a ski resort on Lone Mountain. Huntley promised Big Sky would be “the greatest thing that ever happened to Montana.” He meant not only great skiing, but a thriving economy from a clean industry. In August of 1969, Huntley asked Montana Governor Forrest Anderson to let him use the name “Big Sky of Montana” for his new ski resort. He had to ask for permission because Pulitzer Prize- winning author A.B. “Bud” Guthrie, who penned the novel “The Big Sky” in 1947, had given the rights to the state of Montana. “That’s when the governor picked up the phone and instructed [secretary of state] Frank Murray to give Chet the “Big Sky” name,” writes Ed Homer, a Chrysler VP who worked closely with Huntley, in his sketchbook, “Chet Huntley’s Big Sky Montana.”

Homer describes that time when the idea for Big Sky was coalescing. After a tour up Lone Mountain in 1970, the Big Sky board of directors had their first meeting and elected Huntley as the chairman. “Nothing I’ve ever done, or seen, or accomplished—including [watching] Alan Shepard’s first space ride from Cape Canaveral— compares to my happiness in launching Big Sky,” Huntley said.

In the 1970s, Huntley and his investors bought former homestead properties from private landowners, including the Crail property, and acquired other parcels from Burlington Northern as part of a series of hotly contested land exchanges between the railroad and the United States Forest Service.

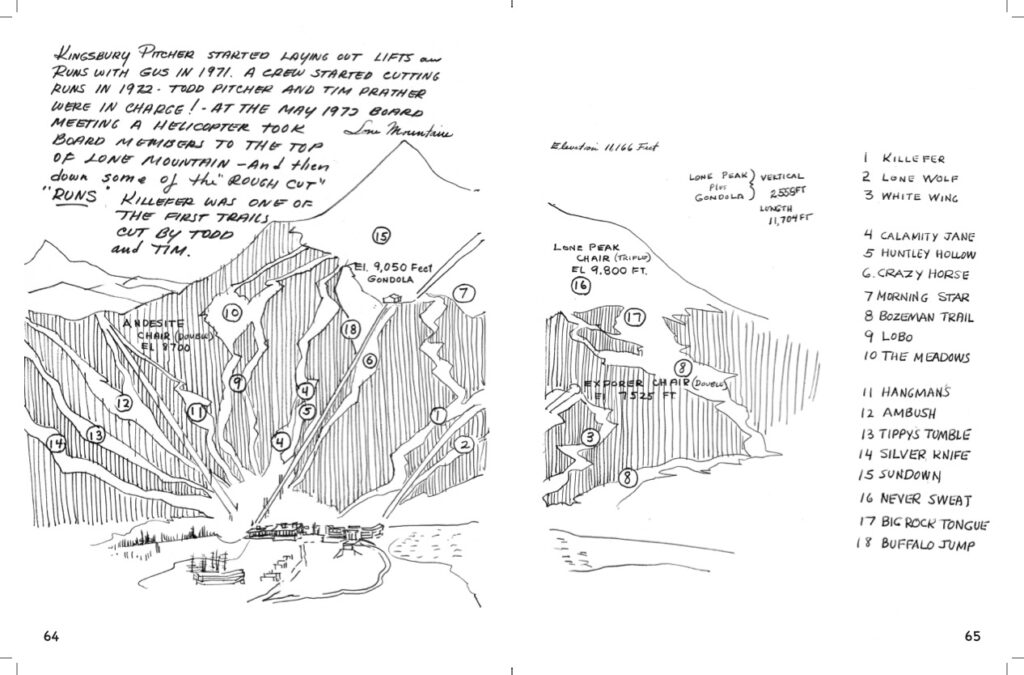

The resort opened in the fall of 1973, with four lifts—Andesite, Explorer, Lone Peak, and a gondola. The runs Huntley’s Hollow and Tippy’s Tumble were named for the resort’s first couple. Before the runs were cut, French Olympic ski racer Jean-Claude Killy had been dropped in by helicopter to assess the bowl on Lone Mountain and the slopes on Andesite. He proclaimed the skiing “magnifique!”

In the ensuing decades, much of the private land now occupied by Yellowstone Club, Moonlight Basin, and Spanish Peaks was still owned by Burlington Northern’s spin-off timber company, Plum Creek, which clear-cut the land to the ground. Another series of land swaps in the mid- ’90s by developers created a continuous swath of private land for development. Today, Lone Mountain Land Company is dedicated to restoring the environment as it manages old-growth forest and clear rivers— and the wildlife that depends on that habitat.

1976 to 2023: Everett Kircher and the Modern Resort

In 1976, ski area pioneer Everett Kircher, owner of Michigan-based Boyne Resorts, bought Big Sky for $8.5 million. Like Huntley, Kircher saw the promise of Lone Mountain to the future of skiing. “He was really in love with skiing and the ski business, and a ski resort out West was a long-held dream,” says Molly Kircher, Everett Kircher’s daughter-in-law and Senior VP of Brand Development at Boyne USA. The Kirchers inherited the Huntley Lodge as part of the original sale and built condominium hotels, but the development of the privately owned land around the resort was and is outside of their purview. “Everett Kircher’s focus was skiing,” she says. “The Lone Mountain Ranch was part of the sale, but he declined to buy it at the time. He was concerned that it was going to take focus away from the ski area.” Today, when a hotel goes up near Big Sky, the ski area sees it as a boon. “As we grow, we always need more of a bed base and more restaurants, activities, and amenities for our guests,” says Kircher.

2000 to 2023: Finally, a Town Center

In 1970, three years before the bull wheels started turning at Big Sky, Bob Simkins, whose family opened a lumberyard in West Yellowstone in 1945, predicted that the flat expanse of land where the Big Sky Town Center now sits would someday be valuable. He and Jim Taylor bought (and swapped land for) six square miles from the owners of Sappington Ranch. A second generation of Simkins inherited the land after Bob died in 1993, but it remained undeveloped until the early 2000s. Since then, the 165-acre walkable development, under ownership by Lone Mountain Land Company since 2022, has evolved into a downtown district filled with shops, restaurants, community events, and a hotel.

Present Day: A Dream Realized and Modern Times

In February 1974, just one month before Chet Huntley would pass away, a small group of board members skied up to his home. “I suddenly realized…the Big Sky dream had indeed come true,” Homer wrote in his sketchbook. As they looked out at Andesite and Lone Mountain, Huntley pointed out that, with binoculars, you could see the skiers. “It was Chet’s simple, honest, and direct way of expressing his fulfillment at seeing people…enjoying themselves at Big Sky—people and nature, sharing together.” Chet Huntley succumbed to lung cancer just three days before the official grand opening celebration of Big Sky, but those who knew him say it wasn’t tragic timing. He’d already seen his dream realized.

Today the land where Sheepeaters dropped obsidian arrowheads and where generations of timber companies clear-cut square-shaped parcels has become neighborhoods and a town. The Kirchers continue to modernize the ski area with a new tram to the summit this season, complete with an all-glass viewing platform to capture the views. And in the meadow, where hardy homesteaders and ranchers eked out a living, Town Center is growing up. While some dude ranches remain, nobody ever struck it rich on gold, and ranching was a tough existence at this elevation. But as some of the visionaries foresaw, tourism sustained a community that grew from a settlement to a town.

What might Huntley think of Big Sky’s development today? “People ask me that all the time,” says Kern. “If I had to channel Chet, I think he’d be so excited about the fact that so many people come here to recreate. His entire plan was to share Montana with people.”

To view this article in Big Sky Life, click here.